|

Preview

The

early church did not have long to wait for the impending

events that Jesus, in His final commission, had prepared

them to expect. He had told them to anticipate the

outpouring of the Holy Spirit, which would be

characterized by their being baptized in the Spirit. As

a result of that Spirit baptism, they would then receive

power to proclaim their witness. In this next chapter,

Jesus’ promises were fulfilled. Ten days following

Jesus’ ascension, while in the Temple courts at the

festival of Pentecost, the apostles were baptized with

the Holy Spirit and boldly proclaimed before the

assembled nation of Israel that Jesus is both Lord and

Christ. |

On Sunday, May 24, 33 AD, ten days following the

ascension of Jesus, the festival of Pentecost had arrived. Luke

begins this chapter with a bold proclamation that during this year’s

celebration of Pentecost, the festival had been fulfilled. In Acts

2:1, he purposely chose the term sumpleroo, which means to

“completely fulfill,” indicating that what he is about to relate is

the prophetic consummation of this Biblical feast.

Pentecost. The Feast of Pentecost, or the Hebrew Shavuot,

marks the anniversary of the giving of the Law to the Jewish nation

and celebrates the theophany, or God’s appearance, at Mount Sinai.

Following the events of this chapter, Pentecost will also forever

mark the granting of the Spirit to Jewish believers and celebrate

their indwelling on Mount Moriah, the Temple Mount.

Pentecost is one of the “big three” pilgrimage festivals when, as

during Passover and Tabernacles, every Jewish male is commanded to

worship at the Temple in Jerusalem (Deut 16:16). In Deut. 16:9-10,

the holiday is designated as Hag Hashavuot – “The Festival of

Weeks.” This name, Shavuot, was so designated because seven

weeks, or fifty days, are counted down from the week of Passover

until the arrival of this holiday. Pentekoste, Greek for the

number fifty, was used interchangeably with the Hebrew Shavuot

.

Pentecost is also called Hag Hakatzir, the Feast of Harvest

(Ex. 23:16). This day marks the end of the barley harvest, which

began at Passover, and the initial ripening of the wheat harvest.

During the week of Passover, a sheaf of barley was selected from the

firstfruits of that year’s crop. This sheaf is called the “omer” and

is offered at the Temple. From the point of that offering, a

countdown period of fifty days begins, called “counting the omer.”

At the conclusion of this fifty-day countdown, each family brought

an offering of two loaves of wheat bread to the Temple, baked from

the firstfruits of the wheat harvest. These leavened loaves were to

be waved before the altar of the Lord (Lev. 23:15-22). It is

important to note that these loaves, being leavened, were neither

burnt nor offered on the altar; this would have violated the staunch

prohibition against the offering of leaven, which represents sin. In

fact, some hold that these leavened loaves were representative of

the worshippers’ sinfulness.

This particular Jewish festival is unique, as it is the only one

without a precisely fixed date. The date must be re-determined each

year (Lev. 23:15-16). The Jewish sages have always hated ambiguity

and so, not surprisingly, the issue of this holiday’s date generated

quite a controversy. This was particularly true in the century prior

to the birth of Jesus, although the controversy was still alive at

the time of Acts. It is not surprising that the Pharisees and the

Sadducees, so frequently at odds, bitterly disagreed over the method

of

determining this date.

The controversy arose over the interpretation of one disputed

phrase, “the day after the Sabbath” (Lev. 23:15). The Sadducees

celebrated Pentecost on the fiftieth day from the first Sunday of

Passover week, interpreting the word ‘Sabbath’ in its normal sense,

“Saturday.” According to this method, Pentecost would always fall on

a Sunday. Therefore, although the specific day of the week, Sunday,

was always fixed, the calendar date would shift from year to year.

Alternatively, the Pharisees interpreted the term

‘Sabbath’ in a specialized sense, understanding it as a reference to

the Festival of Unleavened Bread, which occurred on the Jewish

calendar date Nisan 15. Obviously, the day that followed

Nisan 15 was always Nisan 16. Therefore, Pentecost, coming fifty

days later, would always fall on the fixed date of Sivan 6.

Utilizing their preferred method, the Pharisees removed all the

ambiguity as to the specific annual date on the Hebrew calendar,

although the day of the week would shift from year to year.

During the events of the gospels and Acts, the Sadducees were in

control of Temple worship. Therefore, their system of determining

Pentecost’s date was in place, making the events described by Luke

fall on a Sunday. Later, following the destruction of the Temple in

70 AD, the Pharisees’ religious judgments became determinative in

Judaism, and their methodology was employed.

Although not specified in Scripture, Pentecost also came to be

commemorated as zman mattan toratainu, “the season of the

giving of our Torah,” the day on which the Torah was given to

Israel. In fact, the central Scripture reading for this holiday is

the passage that records God’s giving the Torah to Israel and

entering into the Mosaic Covenant with them at Mount Sinai (Ex.

19–20). The events described within this passage of Exodus, and

those events that immediately follow, provide the foundation for

what will be fulfilled in Luke’s narrative.

This Scripture describes the dramatic and awesome manifestation of

God’s presence on Sinai as He thundered the Ten Commandments to His

people, with accompanying lightning, smoke, fire-flashes,

supernatural shofar blowing, and earth quaking. It goes on to

describe Israel’s reaction, as they tell Moses that they had

experienced all of God’s manifest presence they could stand! Hearing

from God had proven to be too intense an experience; they feared

sensory and emotional overload. They instead asked Moses to be God’s

spokesman, to be a “middleman” between God and Israel (Ex.

20:18-19). Moses, ascending the mountain to commune with God,

disappeared for forty days into the midst of the thick, dark cloud

which was God’s manifest presence (Ex. 24:18). In their fear at

Moses’ prolonged absence, the people built themselves a more

tangible, far less traumatic representation to worship -- a golden

calf (Ex. 32:1).

When Moses returned, he condemned the nation for their grievous sin.

In holy indignation, he destroyed the two stone tablets containing

the Ten Commandments (Ex. 32:19). He instructed his own tribe, the

Levites, to kill the idolaters. The Levites struck down three

thousand Israelites before God mercifully restrained them from

decimating the nascent nation (Ex. 32:26-28).

The events of Pentecost described by Luke in this chapter, some

fifteen hundred years after the Sinai experience, are the

God-directed sequel to the foundational events related by Moses.

Coming of the Spirit

(2:1-4)

Luke records that at about nine o’clock on the

morning of Pentecost, the twelve apostles were gathered together in

one place. There is some disagreement, however, regarding exactly

where the “one place” was in which they were gathered and in which

the awesome manifestations of the Spirit’s visitation are

experienced.

The traditional interpretation has presumed that they are still in

the same house that contained the upper room, in which the dealings

described in the previous chapter took place. This is the

immediately previous referent of location and would seem a logical

assumption. Indeed, Acts 2:2 uses the term “the house” to describe

their location. However, if this is the case, and the “one place” of

Acts 2:1 is the upper room, it is difficult to explain why Luke

provides no transitional description which maneuvers the apostles

out of the house, through the city streets and into the Temple

complex, where they are positioned by Luke in Acts 2:5.

A more likely interpretation of the “one place”

where they are assembled is the Temple courts. The term “the house”

was customarily used in reference to the Temple (Acts 7:47).

Furthermore, where else would every Jew in Jerusalem be on this

festive day of pilgrimage and celebration, but gathered in the

Temple courts awaiting a wonderful communal festival meal, an

international Jewish picnic. Most likely, the apostles, together

with the other one hundred and eight believers, were in the area of

the Temple known as Solomon’s Portico, or Colonnade, a favorite spot

of Jesus’ (John 10:23) and, later in Acts, of the apostles (Acts

3:11; 5:12).

Placing the events of Acts 2:1-4 in the Temple courts also answers

the difficulties mentioned above of physically positioning the

apostles from the upper room to the Temple. Furthermore, Acts 2:15

specifies that these events occurred at around 9:00 AM., which was

the designated time of prayer. One cannot imagine that the apostles

would have been anywhere else but the Temple on a festival day at

the hour of prayer!

Another interpretive disagreement stemming from these opening verses

is the identity of the recipients of the supernatural manifestation

of tongues in Acts 2:1-4. To which group does the “all” of Acts 2:1

refer? As with the location, there are two choices here as well.

The traditional understanding has been that the recipients of the

gift of tongues were the full company of the one hundred twenty

believers. While this is possible, it is difficult to reconcile with

the internal evidence of the passage. Luke seems to indicate that

the

supernatural empowerment that morning was only granted to the twelve

apostles.

First of all, the antecedent group, or previous referent, were the

Twelve (Acts 1:26). It must be remembered that what Luke originally

wrote had no chapter divisions or headings, and what he mostly

likely meant by “all” was the newly reconstituted group of the

Twelve, his previous subject.

Second, the tongues-speakers were identified in the text as

Galileans (Acts 2:7). This clearly referred to the apostles, who

were all Galileans, and not the larger group, who probably hailed

from a variety of locations in Israel. Furthermore, Peter, with the

eleven other apostles, responded to their being singled out by the

crowd as drunkards (Acts 2:14). In the next verse, Peter specified

that “these men” were not drunk. Since the group of the one hundred

and twenty contained both men and women (Acts 1:14), and Peter

assuredly did not mean to say that “the men were not drunk but the

women were,” then only the apostles could have received the gift of

tongues in Acts 2:1-4.

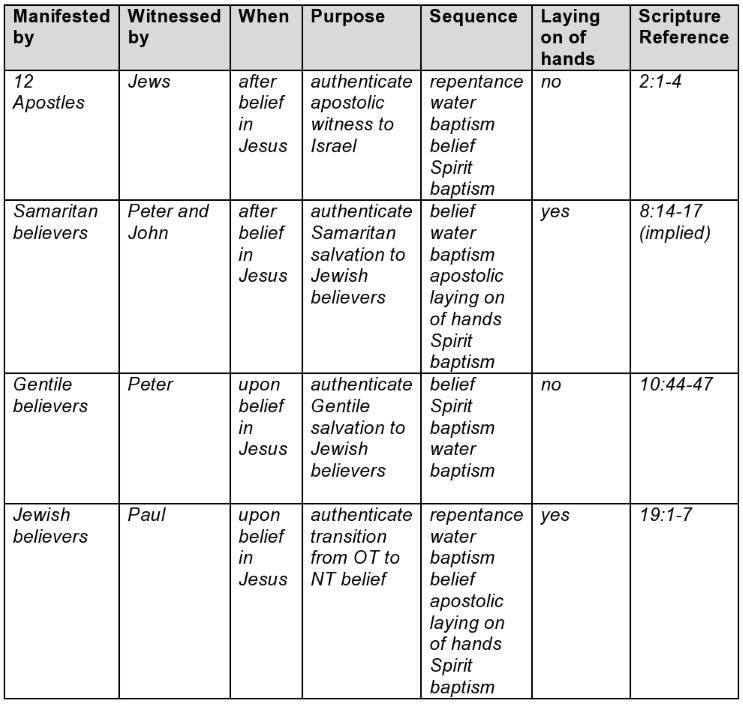

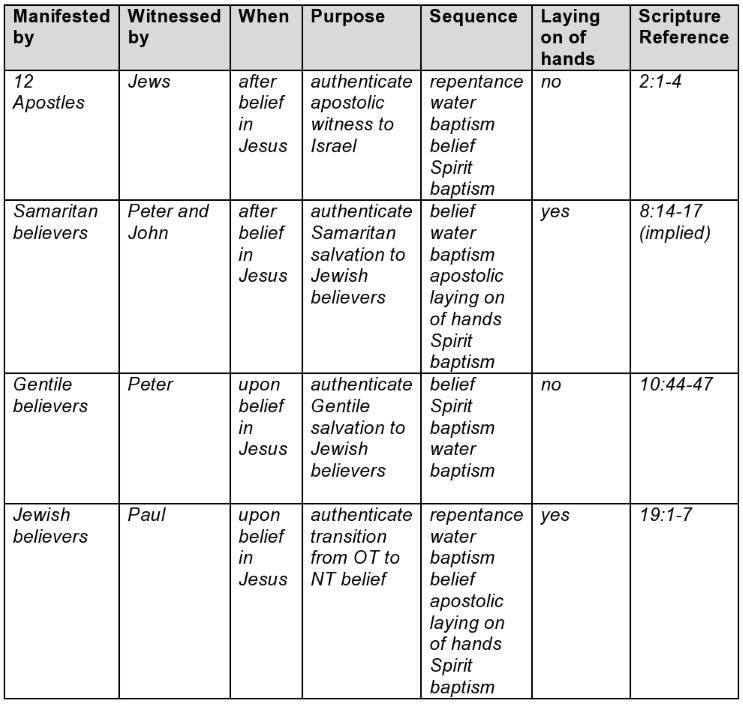

Third, Luke indicates throughout the Acts narrative that the gift of

tongues was given for the purpose of authenticating the apostolic

calling, office and witness. Each of the four recorded instances of

tongues speaking in Acts served this authenticating purpose, either

through the apostles’ exercise of the gift at Pentecost (as in

2:1-4) or through “echoes” of the initial Pentecost experience as

each new group category believed the apostolic message and received

the Spirit (8:14-17; 10:44-47; 19:1-7).

Acts 2:2-4 describes strange, supernatural manifestations that

suddenly and rapidly envelop the disciples. As the apostles were

gathered among the relaxed and joyous crowds in the Temple complex,

a noise resembling a violent wind, one that was heard but not felt,

suddenly filled the Temple. In the Hebrew Scripture, wind, ruach,

the same Hebrew word used for “spirit,” is a common symbol of the

Holy Spirit. One prominent example is the reassembling and

resuscitation of the valley of dry bones in Ezekiel 37, where the

wind represents the Spirit of God, the prophesied instrument of

Israel’s national restoration.

This was followed by a supernatural pyrotechnic display. A sizable

mass of something resembling fire appeared, clearly visible yet not

physically felt, which then began swiftly dividing and cutting

itself up in pieces, distributing one “tongue” of fire to rest upon

each of the apostles. The Holy Spirit, the Ruach Hakodesh, had

dramatically arrived.

Luke’s description of this manifestation resembles

the description of God’s Shekinah glory manifest on Mount Sinai (Ex.

19:18) and filling the Temple upon its dedication (2 Chron. 5:14).

The Holy Spirit was once again gloriously manifesting Himself in the

midst of Israel.

Philo, the first century Jewish historian, in describing the giving

of Torah at Mount Sinai, emphasized both the fire of God and the

language of God in communicating His will to His people.

“And a voice sounded forth from out of the midst of

the fire which had flowed

from heaven, a most marvelous and awful voice, the flame

being endowed with

articulate speech in a language familiar to the hearers,

which expressed its words

with such clearness and distinctness that the people

seemed rather to be seeing

than hearing it.” (14) |

This was a direct fulfillment of John the Baptist’s

prophecy that the Messiah would baptize with the Holy Spirit as well

as with fire (Matt 3:11). This also fulfilled Jesus’ promise, given

some seven weeks earlier on Passover at the Last Supper, that He

would send the Comforter, the Teacher (John 14:26; 16:7-15).

Additionally, this was the empowering event that Jesus had told His

apostles to anticipate (Acts 1:4-8).

The pouring out of God’s Holy Spirit on Pentecost would have been

profoundly appreciated by Jewish recipients. The anniversary of the

divine gift of Torah was the most eloquent of moments for the

revelation of the divine Spirit. This was indeed the logical sequel

to the Sinai experience. The God who came near on Sinai had now come

ultimately near as He indwelled believers with His Spirit.

The Spirit’s presence at Pentecost was marked by three similar signs

also experienced at Sinai: violent wind, fire, and supernatural

sounds. In Acts 2:1-3, Luke described the wind and the fire. In 2:4,

Luke will begin his description of the “supernatural sounds” of this

Pentecost.

The result of this outpouring of the Spirit was the apostles’ newly

acquired supernatural ability to communicate “with other tongues;”

in known, intelligible spoken languages. What Luke means when he

relates that “the Spirit gave them utterance,” is not that the

Spirit Himself is speaking, but that He is providing their ability

to speak. From this point on, the apostles would be empowered to be

the witnesses whom Christ had commissioned.

On this Pentecost, it can be said that there was indeed something

new under the sun! Those Pentecost worshippers were witness to the

birth of the church, the beginning of a new era. From this point on,

all believers would be permanently indwelt by the Spirit, forever

united with Christ and each other.

Filling and baptism. The “filling” of the Spirit is not

synonymous with the “baptism” of the Spirit. Although Luke combined

them in Acts 2:4, these are actually two distinct ministries of the

Holy Spirit. Although only the “filling” of the Spirit is

specifically mentioned here, the “baptism” of the Spirit was also

simultaneously taking place. Luke does not use the specific

technical term, “baptism of the Spirit” in Acts 2:4 to describe

these events, substituting instead a description of the apostles

being “filled” with the Spirit, which emphasizes the controlling

aspect of the Spirit’s ministry.

However, this event would subsequently be recognized by the apostles

as the fulfillment of what Jesus had promised would take place

within a few days’ time (Acts 1:5) as well as the inauguration of

the Spirit’s ministry of baptism, indwelling and filling (Acts

11:15-16).

The filling of the Spirit refers to being under the

control of the Spirit (Eph. 5:18), resulting in a holy lifestyle of

mature spirituality as well as empowerment for ministry (Acts 2:4;

4:8, 31; 9:17; 13:9). In Acts, the primary ministry the Spirit is

shown empowering is that of evangelism, witnessing of the Messiah.

It is a repeatable event (Acts 4:8, 31; 6:3-5; 7:55; 9:17; 13:9, 52)

that both Old and New Testament believers experienced, although it

was much rarer in the Old Testament (Ex. 31:3; 35:30-34; Num

11:26-29; 1 Sam. 10:6-10). Believers cannot generate the filling of

the Spirit, but they can and should purposely yield themselves to

the filling of the Spirit (Eph. 5:8). The primary result of the

Spirit’s filling in Acts is empowerment for effective ministry.

In contrast, the primary result of the baptism of the Spirit in Acts

is organic union with Christ and His Church (1 Cor. 12:13). It is a

onetime, non-repeatable event in which each new believer is

supernaturally united with Jesus and joined together with every

other fellow believer. This organic union occurs at the moment of

trusting Christ as Messiah (Rom. 8:9; 1 Cor. 12:13). This is not an

experience one can either yield to or resist. One cannot actively

trigger spirit baptism; one may only be the recipient of the

sovereign work of God. The ongoing consequence of Spirit baptism is

that believers subsequently experience the unending, continual

indwelling of the Holy Spirit (John 14:16; 1 Cor. 6:19).

Scripture records three atypical examples of Spirit baptism

occurring at a significantly later time than initial belief. All

fall within the Acts narrative (Acts 2:1-4; 8:17; 19:6). These

instances, however, serve respectively to authenticate the ministry

of the apostles (2:1-4), authenticate Samaritan salvation (Acts

8:17), and authenticate the ministry of Paul (Acts 19:6).

Tongues. The word that is translated as “tongues” in Acts 2:4

and 2:11 is glossa, the common Greek word for the physical

organ of speech. It is also used metaphorically for speech, or

language, itself. That glossa is used in the sense of

“language” in Acts 2 is confirmed by Luke’s alternate use of the

Greek term dialekto, “known language” or “dialect,” in Acts

2:6 and 2:2:8. Further confirmation that known languages are being

described is Luke’s description of the tongues to be heterais,

“of a different and distinguishable kind.”

Therefore, as described in Acts, tongues has long been understood to

be recognizable languages supernaturally granted to serve as

authenticating confirmation of the apostolic message. (15) Without

exception within Acts, this authenticating confirmation provided by

the four recorded episodes of tongues speaking is before a Jewish

audience (Acts 2:4-11; 8:17; 10:46; 19:6). Later, Paul elaborates

that the gift of tongues was the fulfillment of the prophet Isaiah’s

depiction of an authenticating sign for the Jews (Is. 28:11; 1 Cor

14:21-22).

Since every person in the Temple crowd, including the apostles,

could normally converse in Aramaic, Hebrew or Greek (and most were

conversant in two out of the three languages), then the purpose of

speaking in tongues at Pentecost could not have been to facilitate

communication between the apostles and the crowd. The apostles’

speaking in a multiplicity of languages would neither have added to

their efficiency nor the crowd’s edification. The gift of tongues at

Pentecost had the sole purpose of serving as a colossal beacon to

the gathered multitude that God Himself wanted their attention.

There was something vital of which He wanted them to be aware.

In the entire narrative of Acts, it is only in the

apostles’ initial ministry to the Jews (Acts 2:1-4), Samaritans

(Acts 8:17), Gentiles (Acts 10:44), and transitional believers (Acts

19:6) that the phenomenon of tongues is experienced. This is strong

indication that, at least within Acts, tongues was a sign given by

God to authenticate a new work of salvation (Heb. 2:4). It was,

therefore, limited to the initial outpouring at Pentecost plus the

three separate “echoes” of Pentecost that follow, as old boundaries

were newly broken through by the Spirit. It is of note that in none

of these four special instances was the gift of tongues an

indication of a “second” or “additional” Spirit baptism,” or a

“second work of grace” (see Table 8).

Table 8. Echoes of Pentecost: Tongues in Acts

Results

of the Coming of the Spirit (2:5-13)

As Pentecost was a pilgrimage festival, the Temple

was filled to overflowing with huge crowds of pilgrims from all over

Israel and the Jewish diaspora as well as the cosmopolitan residents

of Jerusalem. Due to the difficulties and expense of travel to

Jerusalem, particularly for those who lived outside the land of

Israel, vast numbers of Jews stayed in Jerusalem for the fifty-day

period between Passover through Pentecost. This was the only

two-month period in the year when the holy city would be packed with

so many people. Therefore, this period was particularly strategic

for facilitating the news of Jesus’ crucifixion and resurrection as

well as for the apostolic witness.

Luke described the wind and fire as occurring with such rapidity

that by the time anyone other than the apostles or their comrades

noticed them and turned their heads to look, they were already gone.

Yet if most of the Temple crowd missed the initial rush of the

Spirit’s coming, the result of His visitation, the empowered

apostolic utterance, was inescapable.

Luke specified that the crowd was composed of particularly “devout”

Jews. These were part of Israel’s faithful believing remnant,

written about later by Paul (Rom. 11:5). Since they were faithful to

the revelation that they had heretofore received from the Hebrew

Scriptures, they would naturally prove responsive to this new

revelation. They came rushing over to hear Peter and the apostles

speaking in a multiplicity of dialects. Luke reports the crowd’s

response. At first the crowd was bewildered (Acts 2:6). Their

bewilderment grew to amazement and astonishment (Acts 2:7). The

apostles were speaking in the “mother-tongues” of many diaspora

Jews. One can only speculate as to what the actual content was that

the apostles were proclaiming in these various languages! All Luke

records is that the apostles were extolling God’s greatness and

speaking of His “mighty deeds” (Acts 2:11).

Whatever it was that they were so animatedly and enthusiastically

proclaiming, the crowd recognized them as being Galileans. In first

century Israel, Galilee was considered to be the boondocks of

Israel, and Galileans were considered to be uneducated, country

bumpkins, with strong, guttural accents (Matt. 26:73; Mark 14:70;

Luke 22:59). Apparently, whether speaking in tongues or not, the

apostles retained their accents! The crowd would naturally have

wondered how they were able to speak so many foreign languages with

such fluency.

There is an ancient rabbinic legend in the Midrash, which states

that as God gave the Torah to Israel at Mount Sinai, all nations

throughout the world simultaneously heard God's voice in their own

languages. Similarly, on Mount Moriah that morning, as Peter and the

apostles preached, Jews from all the nations heard the word of the

Lord in their own languages. This, however, was no legend.

The crowd contained representative Jews from a variety of diaspora

nations and regions. Luke’s selected representative list of visitors

sweeps like a compass around Jerusalem, the geographic center of the

Jewish diaspora as well as the Roman Empire, (16) from east to north

to west to south, and includes visitors from the regions of Persia

(Acts 2:9), Asia Minor (Acts 2:9-10), North Africa (Acts 2:10),

Europe (2:10-11) Arabia (Acts 2:11), and, of course, Israel (Acts

2:9). When Luke mentions the Roman contingent, however, he pauses to

particularly specify that this group contained both Jews and

proselytes, Gentiles who had converted to Judaism (Acts 2:10).

Perhaps Luke is foreshadowing the eventual climax of the Acts

narrative in Rome, or it is possible that members of this Roman

contingent, subsequent to Pentecost, were the founders of the Roman

church.

Having listened for some time now to the apostles’ dazzling display

of linguistic fluency, the crowd was, by now, thoroughly confused

and simply did not know what to think. Luke writes that they were

“amazed and greatly perplexed.” In other words, they were flummoxed,

and the crowd’s response was mixed. One group responded with intense

curiosity. They seem to have recognized that there was a miracle

occurring right before their eyes, or ears in this instance, and

they pondered its meaning and significance (Acts 2:12).

A second group exhibited an opposite response. They

scoffed and mocked the apostles, accusing them of being too

enthusiastic in their consumption of new, or sweet, wine. In other

words, they accused the apostles of being drunk (Acts 2:13). “Sweet”

or “new” wine was the very sweet and highly intoxicating batch of

wine that had not yet completed the fermentation process.

Drunkenness was frowned upon in ancient Jewish culture, so an

accusation of drunkenness, particularly so early in the morning and

in the Temple on the festival day, would have been a particularly

derisive accusation.

Based on this accusation, there must have been something about the

apostles’ manner and body language which suggested drunkenness. The

allegation of “drunkenness” cannot be derived from their speech. As

Luke has manifestly described, they were

speaking articulately in languages that were understood by the

crowd, so simultaneous ecstatic utterances cannot be in view.

Rather, it perhaps should be assumed that the intensity of this

inaugural Spirit baptism proved to be slightly overwhelming to the

apostles. Just as experiencing God had been overwhelming for the

Israelites at Mount Sinai (Ex. 20:19), the outpouring of His Spirit

may have been a bit shocking to the apostles’ frail and limited

human nervous systems.