|

You will receive power when

the Holy Spirit has come upon you; and you shall be My witnesses

both in Jerusalem, and in all Judea and Samaria, and even to the

remotest part of the earth.

~ Acts 1:7-8 ~

|

*

Every so often, a commentary comes to the attention of the

student of Scripture that strikes him or her as being head and shoulders

above the crowd. Steven Charles Ger's Acts: Witnesses to the World

has struck this editor and AMC's board secretary Mottel Baleston in just

such a way. For this reason, we have decided to present Acts in its

entirety - not just for the wealth of information that may be gained

from its study, but, as Mottel stated, as a model for how a Bible study

ought to be done. Has God given you the gift of teaching? Perhaps you'll

be next to pick up the torch for this level of teaching. ~ editor

*

INTRODUCTION: BACKGROUND TO ACTS

Part 2 of 3

Links to previous increments of Acts:

Witnesses to the World

may be found in our Library.

*

PURPOSE OF

ACTS

Perhaps as many as a dozen plausible

reasons have been proposed over the centuries to

explain the occasion of Luke's writing of Acts. Countless students have

valiantly, but

futilely, applied themselves to the task of narrowing down the list to

one overarching

purpose. Yet to limit Luke to only one purpose does injustice to his

broad and

monumental work. Although addressed to only one individual, his patron,

Theophilus, it

must be recognized that Luke wrote with multiple purposes in mind. It is

possible to

ascertain, upon analysis of the Acts narrative, four particularly

compelling purposes.

Historical: The primary purpose of Luke's work is historical. It is the

sequel to his

gospel, which was the chronological account of Jesus' earthly ministry,

and Acts resumes

with the record of Jesus' continued ministry through the agency of His

apostles (1:1).

Luke wrote this account to carefully and systematically trace the growth

and geographical

expansion of the church over its first three decades (2:47; 5:14; 6:7;

9:31; 12:24; 16:5;

19:20). While acutely selective in his choice of material, Luke provides

every necessary

historical highlight to understand the development of the church from

its origins in

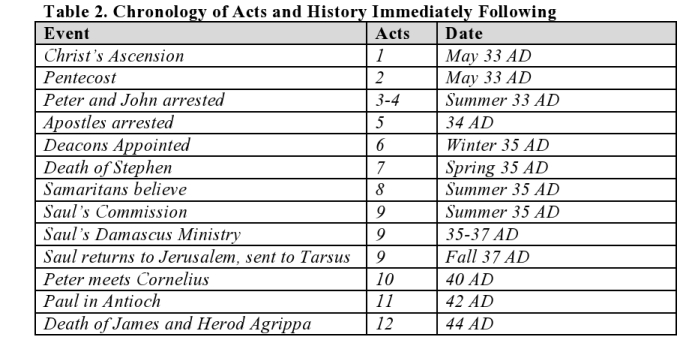

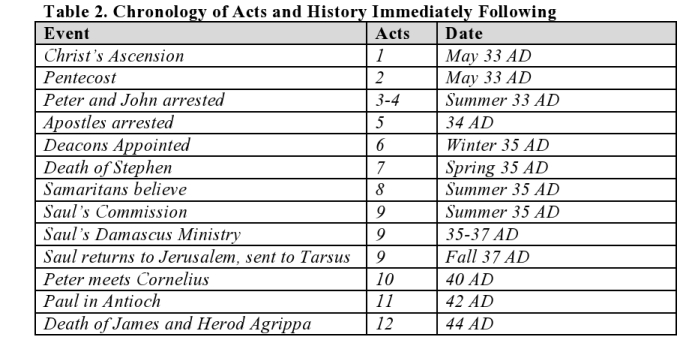

Jerusalem through its climactic extension to Rome (see Table 2).

Theological: Luke's purpose went far beyond the historical. Another

purpose Luke

has is theological in nature. He wrote Acts to validate that

Christianity is the legitimate

development of God's plan and program for both Jews and Gentiles as

engineered by the

Holy Spirit (1:5-8; 2:1-47; 5:1-11; 6:5; 8:14-17; 10:44-47; 13:1-4;

19:1-7). Luke reveals

the continuity between what God had promised to Israel through covenant

and prophecy

and what has been received by the church.

Luke also carefully demonstrates that God's promises to Israel have not

been

exhausted by the initiation of the church age. Although only a Jewish

remnant has

currently accepted their messiah and at present the nation stands in

opposition to him, at

some point in the future Israel will acknowledge Jesus as their Lord,

savior and king

(3:21).

Acts, however, is not a theological treatise. It must always be

remembered while

studying Acts that Luke is not concerned with developing doctrine. This

is a book of

historical descriptions, not propositional prescriptions. His intent was

not to make

normative for all believers through all time the unique and unrepeatable

experiences of

Pentecost, Saul's Damascus Road encounter, or to standardize various

apostolic

decisions, miracles and judgments.

As a historian, Luke is concerned with the practical application of

these new and

unprecedented theological developments. He defines the nature,

structure, and practices

of this new community of believers. He describes the relationship of

this community to

its adherents, to the unbelieving and often hostile Jewish community, to

the Temple, in

Judaism in general, and to the power of the Roman Empire. Finally, he

relates the only

major theological controversy to arise within the first three decades of

the Church, that of

Gentile inclusion into the church on an equal basis with Jews.

Apologetic: Luke also writes with an apologetic purpose in mind. He

proves that,

while the Jewish leadership consistently opposed the Christian movement

from the start,

the Roman civil authorities demonstrate no such antagonism (13:12;

16:39; 18:15-17;

19:37-40; 24:23; 25:19-25; 26:31-32; 28:30-31). Although Judaism viewed

Christianity

as an ominous and menacing sect, the Roman Empire perceived no such

threat from the

burgeoning movement, despite the fact that its founder had been executed

as a criminal

by Rome.

Luke assembles a thorough stream of evidence to establish that

Christianity was not a

political movement, but primarily a religious one; a movement with a

profound Jewish

heritage and deeply rooted in Hebrew Scripture. Therefore, by

highlighting Christianity's

Jewish association, Luke sought to demonstrate that the new faith should

share Judaism's

status as a recognized, legally accepted religion within the Empire.

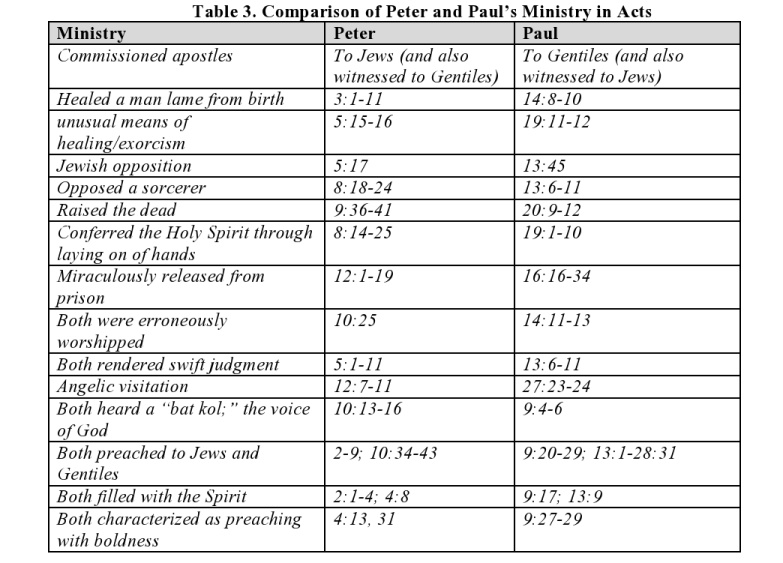

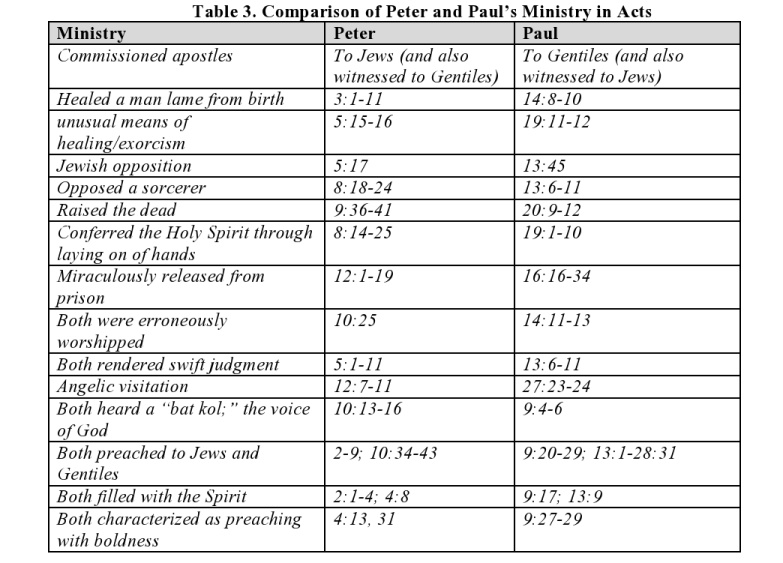

Biographical: Luke's final purpose is a biographical one. In Acts, Luke

firmly

associates Paul's apostolic ministry with the apostolic ministry of

Peter. By developing

this strong literary connection between Peter and Paul, Luke

demonstrates the full

apostolic authority of Paul. Time and again, example upon example, the

record of Acts

reveals that whatever Peter was empowered to do, Paul was so empowered

as well. Luke

carefully presents these two men as absolute equals in supernatural

ability, apostolic

gifting and divine commission (see Table 3).

THEME

AND STRUCTURE OF ACTS

The theme, or "big idea," of Acts

emanates from the crucial opening passage in the book,

which contains Jesus' commission to his apostles,

you will be My

witnesses in

Jerusalem, and in all Judea and Samaria, and to the ends of the earth

(Acts 1:8). This

central idea combines each of Luke's four purposes into one coherent

whole: identifying

message (witness of Jesus, i.e., the gospel), messenger (the apostles)

and location of

delivery (Jerusalem, Judea and Samaria, the ends of the earth).

With adroit literary skill, Luke uses this divine apostolic commission

to organize his

book in two major ways: geographical and biographical.

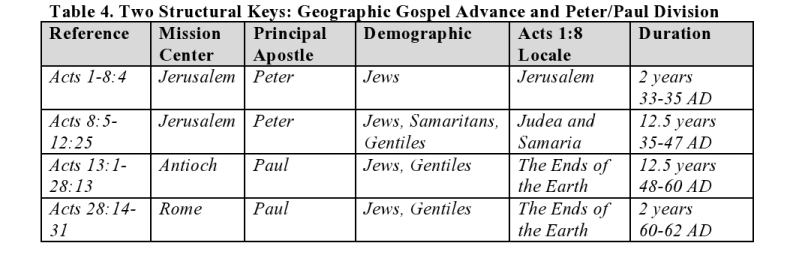

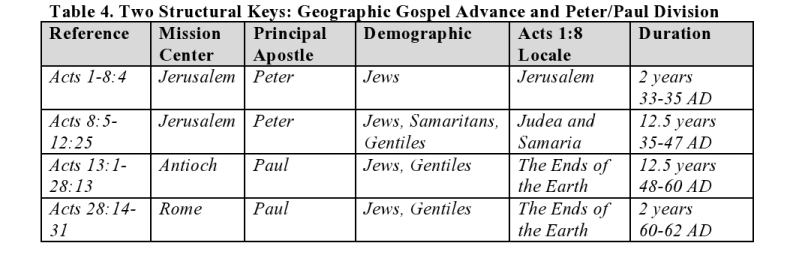

Luke's geographical structure arranges the book according to the

location of the

gospel's delivery, from Jerusalem (1:1-8:4) to Judea and Samaria

(8:5-12:25) and to the

ends of the earth (13:1-28:31).

Luke's biographical structure neatly divides the book into two parts,

which are mirror

images of each other (1:1-12:25 and 13:1-28:31). While the second half

of Acts is longer

in verbal content than the first (more chapters and verses), Luke has

arranged both halves

to be equal in chronological content. Luke has broken his coverage of

the first twenty-nine years of church history into two equal parts consisting of

fourteen-and-one-half

years apiece.

Additionally, each fourteen-and-one-half year historical period has its

own "leading

man," the principal apostle with whom the narrative is concerned

throughout that period;

first Peter, then Paul.

He further subdivides each fourteen-and-one-half year period into a

twelve-and-one-half year and a two-year period. The two-year periods bracket the Acts

narrative. The

story begins with the first two-year period (1:1-8:4) and takes place

solely in Jerusalem,

the birthplace of the church. Luke expends seven chapters relating this

defining stage in

the church's history. The two-year period which concludes the book

(28:14-31) takes

place solely in Rome, the geographic goal of Paul's apostolic witness.

Luke summarizes

this final stage in only half a chapter.

The core of the book takes place within the two twelve-and-one-half year

periods and

chronicles the gospel's transition from Jerusalem to Rome. It also

shifts the apostolic

focus from Peter to Paul (see Table 4).

The key word in Acts is "witness," martus, and is used twenty-one

times in Acts.

This was to be the main function of the apostles and their associates.

THE FIVE TRANSITIONAL

CIRCUITS IN ACTS

Acts is a unique component within the

NT corpus. It is only the book of Acts that

recounts the historical record of the church's first three decades. The

evolution fromsmall Jewish sect to universal movement was not always smooth. The

history of apostolic

activity serves as a transition between the resurrection of Christ and

our own post-apostolic era. Acts serves as the bridge over the following five

transitional pathways, or

circuits.

First, there is a historical transition as the repercussions of Jesus

passing over the

mantle of His ministry to His closest followers are traced. The book of

Acts records the

developing apostolic application of the ministry of Jesus.

Second, there is a cultural and geographic transition as the church

developed from

its initial Jewish milieu to its eventual expanded, international scope.

It was a long road

from Jerusalem to Rome, and Acts records the essential elements of that

journey.

In Acts, we see the circumstances by which the door to the original

Jewish

community of believers is unlocked to Gentiles. We learn how spiritual

equality was

established and recognized between Jews and Gentiles within the

broadened community

of faith. In Acts, we are privy to the theological difficulties and the

very practical

obstacles to Gentile equality with which the Jewish community needed to

wrestle and

ultimately overcome.

In Acts, we also see the paradox inherent in such a specifically Jewish

message being

rejected by the majority of Jews, yet accepted so willingly by Gentiles

who lacked any

biblical background or education.

There is also an evangelistic directional transition, with the nation of

Israel evolving

from the point of terminus in finding God to its serving as the point of

departure. In the

Hebrew Scriptures and the gospels, a centripetal ministry is modeled,

where Israel is the

center of God's activity, and one who seeks Him must necessarily come

through the

Jewish people. In Acts, God's activity diffuses, and the rotation of

outreach has reversed

to one of centrifugal force, where representatives from Israel spin out

into the world,

bringing God to the nations. The narrative traces a steady progression

outward from

Jerusalem, through Israel and to the nations. This was not always a

natural or willing

transition, and circumstances often provided the catalyst to make this

transition.

In addition, there is a theological transition, which moves the church

from the

personal presence of Jesus to the personal and internal presence of the

Holy Spirit. As

Jesus directed his apostles throughout His earthly ministry, Acts

records the Spirit's

direction and guidance of the church. With 2000 years difference between

the twenty-first century and the first century, it is sometimes difficult to

appreciate just how radical it

was for this movement to succeed without the physical presence of its

founder and leader.

There is a major difference between Jesus being among believers and the

Holy Spirit

dwelling within believers. Acts records the unprecedented genesis and

consequence of

this divergence.

In addition, Acts records the movement away from the Law as a way of

life and

means of relating to God, to that of grace. Following the resurrection

and exaltation of

Jesus, the Mosaic Law has been abrogated (Acts 15:1-29). (6) A new

dispensation had

dawned, characterized by the law of Christ, not Moses (1 Cor. 9:21; Gal.

6:2). Almost

from the beginning, the early church was accused of preaching that, in

some fashion, the

Law had been nullified as a way of life (6:11-14; 18:13; 21:21).

The ramifications of Jesus' resurrection and exaltation as Messiah and

the subsequent

creation of a new entity, the church community, would force what had

begun as a Jewish

sect to necessarily make the painful break away from the Jewish

religion. Acts traces the

church's break with Judaism from original fracture (4:1-2) to gaping

chasm (25:2-3).

While the church broke from Judaism as a system, it did not break from

Israel as a

nation. As the Acts narrative concludes, the church is still heavily

Jewish in character.

The abrogation of the Law does not imply that the early church abandoned

the Law

wholesale or ceased observing Jewish customs and traditions (Acts

21:20). The early

church regularly attended Temple (2:46; 3:1) and synagogue (13:14),

observed the

Sabbath (15:21) and circumcision (16:3), and performed ceremonial vows

(18:18; 21:24).

Only gradually, over its first decade and a half, did the church as a

whole begin to

realize that the Law of Moses was no longer operative as the standard

way of life for

believers. This revolutionary transition slowly came to be understood

with the

incorporation of Gentiles into the church (11:1-18). Gentiles did not

need to become Jews

prior to becoming Christians.

The Mosaic Law, however, did not cease to be recognized by the early

church as

Holy Scripture, God's divine revelation. It continued to be their

central basis of

instruction, guidance, and source of messianic prophecy. In fact, the

Law's greatest

purpose for the early church was in its prophetic testimony of the

Messiah. It contains the

promises of the Messiah, now fulfilled in Jesus (Acts 3:13, 22-23;

24:14; 26:22-23).

Finally, there is a christological transition, which moves Israel and

the world from

an anticipated messiah to a returning messiah. With the death and

resurrection of Christ,

God's expectations of His people Israel and of the nations undergo a

radical adjustment.

Although, from the beginning, salvation has ultimately always been by

grace through

faith, the specific content of that faith develops over time with each

new revelation. Since

the dawn of the church age, following the resurrection and ascension of

Jesus, salvation is

solely through faith in Him. Acts records the passion of the apostles as

they energetically

broadcast the new requirements for the salvation of Jew and Gentile

alike.

This relates to the final aspect of Acts' christological transition, the

generation of

devout Jews and God-fearing Gentiles whose lives spanned the period

prior to and

following Christ's resurrection. Similar to the generational torch which

passed during

Israel's forty year wilderness sojourn, there was a transitional period

of apostolic activity

which roughly extended until the death of the final member of the

generation which came

of age prior to Christ's resurrection.

FOOTNOTES

6. Darrell L. Bock, “A Theology of Luke-Acts,” in Roy B. Zuck and

Darrell L. Bock, eds., A Biblical

Theology of the New Testament (Chicago: Moody Press, 1994), 138.

STUDY

QUESTIONS

3. List four purposes of Acts.

4. Describe the theme and structure of Acts.

5. Describe the five transitions of Acts.

*

Acts: Witnesses to the World

Copyright © 2004, Tyndale Theological Seminary