|

You will receive power when

the Holy Spirit has come upon you; and you shall be My witnesses

both in Jerusalem, and in all Judea and Samaria, and even to the

remotest part of the earth.

~ Acts 1:7-8 ~

|

*

Every so often, a commentary comes to the attention of the

student of Scripture that strikes him or her as being head and shoulders

above the crowd. Steven Charles Ger's Acts: Witnesses to the World

has struck this editor and AMC's board secretary Mottel Baleston just

that way For this reason, we have decided to present Acts in its

entirety - not just for the wealth of information that may be gained

from its study, but, as Mottel stated, as a model for how a Bible study

ought to be done.

Has God given you the gift of

teaching? Perhaps you will be next to pick up the torch for this level

of teaching.

We will begin with the first half of Steven's very

informative introduction to the Book of Acts; but first, Steven's

dedication and a little bit about Steven himself.

Dedication

To my wife, Adria Lauren, whose worth

is far above rubies and who reassuringly certified that my ramblings

made sense; and to my son, Jonathan Gabriel, our five-year-old gift from

God, who impatiently waited for his Dad to get his nose out of this book

to come play with him.

About the Author

Steven Ger grew up in a Jewish family

in Brooklyn, New York and Aberdeen, New Jersey, where he was educated in

both church and synagogue due to his distinctive heritage as a Jewish

Christian.

He is the founder and director of Sojourner Ministries, an organization

dedicated to exploring the Jewish heart of Christianity with both Jew

and Gentile. The name of the ministry is derived from the Hebrew meaning

of Steven's surname. In Hebrew, the word "ger" means sojourner or

wanderer. This particular "wandering" Jew's faith journey has led him to

the conviction that Jesus is the Messiah who was foretold in the Hebrew

Scriptures. Steven's life is dedicated to helping people see their

Messiah more clearly through Hebrew eyes.

Steven is the former host of the North Texas weekly radio show, The

Jewish Heart of Christianity, and is uniquely equipped to comment on

Israel, Judaism and the Church. He has appeared as a guest expert on

both radio and television. He is also the host of an hour-long teaching

video showing how Christ's reinterpretation of the Passover meal

instituted the celebration of communion and announced a new era in human

history.

Television audiences and church

congregations alike have enjoyed Steven's leading them in invigorating,

contemporary messianic worship. He is an accomplished singer, pianist

and songwriter whose composition, "Jeremiah 31", was recorded by

The

Liberated Wailing Wall.

Steven has led 11 tours to Israel, with extensions to Egypt, Greece,

Jordan, Turkey and Germany. He has lectured at Dallas Theological

Seminary and at Tyndale Seminary. He served for 7 years as Director of

Worship/Education at Providence Church in Rowlett, Texas.

He earned a BA in psychology and interpersonal communications from

Trenton State College and a Th.M from Dallas Theological Seminary.

Steven lives in the Dallas area with his wife, Adria, and their son,

Jonathan Gabriel.

*

INTRODUCTION: BACKGROUND TO ACTS

Part 1 of 3

*

INTRODUCTION TO ACTS

The

book of Acts grants readers a unique and fascinating glimpse into the

world of the

early church. We peer through the corridors of two millennia and see the

still vivid

foundations of our own faith. Beginning in Jerusalem, Acts shows us the

road we

believers have traveled to arrive at our present state. All that we, the

contemporary

church, are today, we owe to the pioneers to whom its author, Luke,

introduces us. Luke

continues to perform an inestimable service for contemporary believers

by unveiling the

historical, social, cultural, political and religious milieu of the

first three decades of

church history.

Indeed, Acts is, at its most basic, a book of history. Yet for so many

of us, the

mention of any sort of history book immediately brings to mind dry,

dusty tomes filled to

overflowing with infinitely irrelevant data from some unrelated, bygone

age.

Acts is not that sort of history book.

In many ways, Acts is the singularly most earthy and accessible book in

the entire

New Testament. It is entirely in its own distinct category. It is not

chock full of

challenging, doctrinal propositions, as are the epistles. It is not

composed of enigmatic,

apocalyptic imagery, as is Revelation. Nor does it consist of the

biography, teaching and

parables of the crucified and resurrected God-man, as do the gospels.

Nonetheless, Acts

provides the necessary context for the New Testament and is the

connecting bridge that

links this collection of gospels, epistles and apocalypse together.

Acts is unique. It is story. A simple story about regular human beings

who are just

like us. They share our same hopes and similar fears; our worst biases

and best qualities.

In fact, Acts is, essentially, our story. It is your legacy and mine. It

is the record of our

brothers and sisters who came before us, blazing a revolutionary,

messianic trail from

Jerusalem to "the ends of the earth."

As you dip your toe into the first few pages of the narrative, you just

may see your

reflection. Perhaps a spark of recognition will be ignited by the

hesitant first steps of a

fisherman who, at long last, emerges as a "fisher of men." Or perhaps by

the strong,

athletic stride of legs, useless for forty years, now miraculously

healed. Could it be that

you relate to the paralyzing chill of being called on to defend your

faith before those who

despise you? Maybe you recognize the initial flood of disbelief as God

answers a prayer

that you considered the utmost of longshots?

We easily identify with the people in Acts because Luke never allows us

to forget

their humanity. It is impossible to confuse Peter or Paul with fictional

characters. No

ancient novelist would ever create men whose lives were characterized by

such dramatic

contradictions: the brash and blustering everyman who blossoms overnight

into an elder

statesman; a movement's most infamous persecutor who develops into its

most

prominent advocate. Luke has drawn two millennia's worth of readers into

the

overlapping apostolic "adventures" of these two first century Jewish men

who, while so

dissimilar, shared a common vision and served the same Messiah.

While Acts is the definitive account of the early church's expansion, it

was not

Luke's intention to provide a comprehensive report on the apostolic

mission to Israel and

the Roman world. To do so would have taken an entire series of sequels

to his original

gospel. At its present length, Acts already approaches an ancient

scroll's maximum

length of between thirty-two and thirty-five feet.

(1)

Luke provides considered selections, chosen from the vast historical

panorama of

early church history. The majority of the apostles barely make a cameo

appearance within

the narrative. Nor does Luke mention their eventual destinations or

destinies. Even Peter

disappears from the narrative after fifteen chapters.

In a series of vignettes, or "postcards," some historical, some

biographical, still others

theological, Acts reveals the successes and defeats, the conquests and

tragedies of the

original band of Jesus' followers. In Acts we are able to share in the

joy, the loss, the

rejection, the confident assurance, the jealousy, the setbacks, the

frustration, the

passionate debate and the ultimate triumph of these pioneers of the

Jesus movement.

These are ordinary people who, through the power and enablement of the

Holy Spirit,

accomplish extraordinary things in the name of their Messiah. In less

than one

generation, three decades, this initial cohort of Christians boldly

"turned the world

upside-down" (17:6)!

The existing literature on Acts is voluminous, and new works are

regularly being

added. I have introduced nothing in this commentary that has not been

previously written

about Acts, most likely with superior style and scholarship.

Nevertheless, commentaries

on Acts written from the perspective of and with the sensitivities

peculiar to a Jewish

Christian are in the distinct minority. Most of the Acts narrative,

however, deals with

specifically Jewish issues, questions, concerns and controversies, which

arose as the

church expanded from its initial Jerusalem borders and Hebrew

boundaries. These issues

and questions are not often examined through Jewish eyes or explained

using Jewish

categories. I believe that providing such a basic cultural insight

facilitates understanding

in the study of this foundational work.

I am a fourth-generation Jewish believer, nurtured in the faith from

birth, whose

family found our Messiah, beginning with my great-grandmother, over

three quarters of a

century ago. This project is an outgrowth of that legacy, and I pray

that this Jewish

Christian perspective may prove of value in studying Acts.

As I cannot be your personal study partner, I submit this volume as my

surrogate to

accompany you on your sojourn through the world of the nascent church.

The following

are the modest study notes of this particular "Hebrew of Hebrews;" the

views of a

messianic Jew as he ponders the book of Acts.

AUTHORSHIP

OF ACTS

The traditional claim that Luke wrote

Acts has been essentially uncontested throughout

the book's history. There is clear internal evidence that Luke is the

author of Acts.

First, Acts was written by the same individual who penned the gospel of

Luke. The

prologues of both books are linked to one another (Acts 1:1 refers back

to Luke 1:1-4)

and both prologues designate the same person, Theophilus, as the book's

intended

recipient.

Second, Acts was written by one of Paul's traveling companions, as is

evidenced by

the famous "we" passages (16:10-17; 20:5-15; 21:1-18; 27:128:16) when,

at certain

points, the author changes narrative voice from third to first person.

Luke was one such

companion of Paul and is mentioned in three of Paul's letters (Col.

4:14; Philem. 24; 2

Tim. 4:11). Aside from Luke, Acts notes another eight companions: Silas,

Timothy,

Sopater, Aristarchus, Secundus, Gaius, Tychicus, and Trophimus. Each of

these men,

however, is mentioned at some point within the context of the "we"

passages, eliminating

for authorial consideration all but Luke. Luke alone is not referenced

by name anywhere

within the "we" passages.

Third, it is an indisputable fact that Luke, as an eyewitness and

participant,

demonstrates exceptional familiarity with Roman law and government. He

is unfailingly

accurate in his use of the proper political terminology for each Roman

official in every

Roman province he mentions. This is no small accomplishment, as titles,

offices and

terminology frequently shifted from time to time, province to province

and, often, from

one administration to another. (2)

For example, in Cyprus, Luke recognizes Sergius Paulus as proconsul; in

Philippi,

which is accurately recognized as a colony, the leadership are called

strategoi (magistrates); in Thessalonica, the leaders are called politarchs; in

Malta, the leader is

called the protos (chief man); in Ephesus, Luke deftly differentiates

between Asiarchs

(religious administrators), the grammateus (town clerk) and proconsuls.

(3)

Therefore, we are on extremely safe ground when we assert Luke to be the

author of

Acts.

LUKE THE MAN

Aside from what facts may be gleaned

from the Acts "we" passages and his triple

mention within Paul's epistles, as noted in the above discussion, very

little is known

about Luke as an individual.

Based upon Luke's literary skill and vocabulary usage, there is no

question that he

was extremely well educated. It comes then as no surprise that Paul

identifies Luke as a

"beloved physician" (Col. 4:14). In the realm of the Roman Empire, there

were only three

major medical schools where Luke may have studied. The three celebrated

university

towns of the ancient world were Athens (in Greece), Alexandria (in

Egypt) and Tarsus (in

Asia Minor, specifically, Cilicia, Paul's hometown). (A fourth

possibility is the small

Greek isle of Cos, which had both hospital and medical school.) (4)

Precisely at which of

these three eminent sites of learning Luke studied is a point open to

speculation (and

imagination as well, if he was educated in Tarsus and, if so, whether he

was there

concurrent with Paul's five year residency, from 37-42 AD [Acts

9:30-11:26].) Of

course, in his medical capacity, Luke could verify the many healing

miracles of which he

was an eyewitness.

There is an ongoing debate over whether or not Luke was Jewish. While

the

overwhelming consensus has always been that Luke was a Gentile, the New

Testament

does not explicitly reveal Luke's nationality. However, in Paul's letter

to the Colossians,

Luke is listed separately (4:14) from Paul's list of Jewish coworkers

(4:10-11). While this

is the sole New Testament hint that Luke was a Gentile, on the surface

this passage

would seem to be conclusive.

There is, however, at least an adequate case to be made for Luke having

been Jewish;

not a native of Israel, but a Hellenistic (Greek) Jew of the diaspora

(if so, he would be the

earliest recorded "Jewish doctor"). First, beneath the surface of Luke's

superb mastery of

Greek literary style, there are indications that, while the author wrote

in Greek, he may

have been thinking in Hebrew. This is indicted by the presence of

Hebraisms (Hebrew

word order, phrases and terminology) scattered throughout the text. An

alternative but

less satisfying way to explain the presence of such Hebraisms in Acts is

that they derive

from the original Jewish sources, either written or oral, which Luke

translated as he

compiled his account.

Second, Luke's exquisite knowledge of Jewish theological issues and

sectarian

parties, familiarity with the Temple, acquaintance with Jewish holidays

and marked

concern for Jerusalem go beyond that of merely a historian's reporting

of the facts. It is

difficult to explain Luke's Jewish expertise and concern by simply

citing the two years he

spent in Israel, from 57-59 AD (Acts 21:8-27:1) or imagining the

quantity of time he

spent personally with his friend, Paul, that noted "Hebrew of Hebrews."

Third, Luke deftly weaves quotations and allusions from the Hebrew

Scripture

throughout his book. His fluency and familiarity with the Law, Prophets

and Writings

reveal a mind saturated in the contents of the Old Testament. Luke's

facility with the

Hebrew Scripture indicates comprehensive study. Such sophistication

simply cannot have

been developed over a limited period.

Fourth, Paul affirms in his letter to the Romans that God entrusted "the

oracles of

God," meaning the Holy Scriptures, to the Jewish people, in

contradistinction to the

Gentiles (3:2; 9:4). Paul seems to be saying that God has appointed the

writing of

Scripture to Jews. Therefore, since the gospel of Luke and the book of

Acts are both

Scripture, Luke must have necessarily been Jewish. Alternatively, Paul

may have been

referring only to the Hebrew Scriptures (the Old Testament).

A probable way to satisfactorily synthesize the evidence, pro and con,

concerning

Luke's Jewish or Gentile status, would be to posit that prior to

becoming a Christian,

Luke was either a God-fearer, a Gentile worshiper of the God of Israel,

or a "proselyte of

the gate," a near convert to Judaism. This would explain Paul having

listed him

separately from the Jewish Christians, Luke's familiarity with Judaism

and the Temple as

well as his facility with the Hebrew Scripture. In addition, it would

clarify the profound

interest in God-fearers that Luke demonstrates throughout Acts.

DATE OF

COMPOSITION

As indicated in the prologue of Acts,

Luke's gospel must necessarily have been written

prior to Acts. Since Acts is the sequel to Luke's gospel, most scholars

hold that one

should assign a date for the creation of Acts only after first

determining a date for the

writing of the gospel. This methodology, while logical, is not the only

approach to dating

Acts. To reverse this equation is equally justified, as the following

will demonstrate.

In Luke's gospel, Jesus graphically predicts the coming destruction of

Jerusalem

(19:43-44, 21:20-24). His prophecy was fulfilled by the Romans in 70 AD.

Due to

extreme bias against accepting the validity of any predictive prophecy,

even that which

originated with Jesus, many scholars assign a date after 70 AD to Luke's

gospel. This

would allow Luke to portray Jesus as predicting something which, by the

author's time,

had already occurred.

Yet presuppositions against the possibility of Jesus' prophetic ability

cannot be

allowed to take precedence over documentary data. There is no other

reason other than

bias against predictive prophecy to accept this late a date for the

composition of Luke's

gospel, and so this late dating must be rejected. Therefore, there is no

compelling

rationale for first assigning a date to the composition of Luke's gospel

prior to assigning

a date to Acts. Indeed, it is easier to first date the creation of Acts

and only then move

backward in time to date Luke's earlier composition of the gospel.

A logical starting point in assigning a date to Acts is the last

recorded event, which

was Paul's two-year long imprisonment in Rome. This two-year term began

in the first

few months of 60 AD. Counting ahead two years makes 62 AD the earliest

possible date

of composition. This much is certain. What remains controversial is the

indeterminate

range between the earliest possible date and the latest likely date of

composition.

It is possible that the Acts narrative deliberately ends as it does

through Luke's own

creative design. Many commentators presuppose that it was his calculated

intention to

complete the account with Paul's arrival in Rome. Therefore, Acts could

have been

composed at any point before Luke's death. If this view is correct, then

one may

comfortably date the composition of Acts anytime between 63 AD and 85 AD

or possibly

even later, since the date of Luke's death is unknown.

However, ending Acts with Paul under Roman house arrest seems an

extremely

unsatisfying manner in which to conclude this majestic chronicle. For

Luke to have

known the outcome of Paul's "appeal to Caesar" (Acts 25:11) and not have

recorded it

for his readers, effectively leaving them up in the air concerning

Paul's fate, is simply not

credible, especially since Luke expends the final quarter of the book on

Paul's arrest and

trial.

A more persuasive case may be made for a date of composition no later

than 64 AD.

There is compelling evidence that the window between 62 AD and the

latest possible date

is extremely narrow, for the following reasons.

First and foremost, when read at face value, Acts seems to bring readers

up to date

with Luke's own contemporary circumstances. In other words, there was

nothing more to

write. Paul still awaited trial, and the church continued expanding,

unabated and

unopposed. Any additional chapters would necessarily have had to wait

until history

unfolded with the occurrence of new events.

If Acts had been written later than 64 AD, it is inexplicable that Luke

would fail to

mention Paul's trial, his release from Roman imprisonment, the first

Roman persecution

of Christians under Nero beginning in 64 AD, the death of Peter that

same year, or the

death of James, the brother of Jesus, two years earlier. If Acts had

been written after 70

AD, it is unfathomable that Luke would avoid mention of Paul's death in

68 AD or the

Roman destruction of Jerusalem and the Temple in 70 AD. The fact is that

Luke makes no

reference to any crucial events that concerned the church after AD 62.

Second, the sole theological controversy Acts records is the debate over

Gentile

inclusion. This debate was only active through the fifth decade of the

first century. It was

finally settled in 49 AD at the Jerusalem Council (Acts 15). By 70 AD,

Gentile inclusion

was universally accepted and this issue no longer controversial. Whether

a Gentile

needed to first become Jewish before becoming a Christian was hardly a

concern for

believers after 70 AD and an unlikely topic on which to expend so much

precious scroll

space.

Third, throughout Acts, the Roman Empire shows no animus toward the

church and

is still impartial, in fact, almost disinterested, concerning the

nascent Christian

movement. Time and again, the Romans do not comprehend the nature of the

Jewish

accusations brought against the church or the ferocity of those

accusations. These

accusations are of a religious, not political nature. Indeed, in most

instances within the

early years, Rome treated Christianity as one more incomprehensible

Jewish sect among

many. This was no longer the case after 64 AD, when the Roman Empire

began to view

Christians as a political and cultural threat.

A fourth reason to assign Acts an early date is Luke's expenditure of a

great deal of

narrative energy in demonstrating Christianity's Jewish roots and

association with the

nation of Israel. Following the initial outbreak of Israel's revolution

against Rome in 66

AD, it would no longer have been prudent to press the fledgling faith's

association with

Israel as dynamically as Luke does in his narrative.

Finally, Acts obviously does not rely on Paul's epistles as a source of

biographical

information about Paul. Luke makes no attempt to correlate his account

of Paul's life

with the apostolic correspondence. Therefore, Acts had to have been

written before

Paul's letters had been collected as Scripture and widely circulated.

Peter's final epistle,

written in 64 AD, recognizes the circulation of Paul's epistles and

their Scriptural

authority (2 Pet.3:16).

Therefore, for these reasons, the composition of Acts may confidently be

dated

between 62-63 AD.

LUKE'S SOURCES

During Luke's extensive travels in

Paul's company, Luke himself was a personal

eyewitness to the events he recorded in Acts. In addition to his

European travels, Luke

also spent two unintentional years living in Israel (21:8-27:1). Upon

their return from the

third missionary journey, Paul was arrested in Jerusalem and imprisoned

in Caesarea for

approximately two years, from the spring of 57 AD through the summer of

59 AD. Luke

remained at liberty in Israel throughout this period.

While Paul was enjoying the Roman procurator's "hospitality," it is

impossible not to

envisage Luke traveling among the churches strewn throughout Israel,

researching his

two books. Luke would have had ample time and opportunity to gather

eyewitness

accounts and personal stories from many of Jesus' original followers and

members of the

early church. In addition to what he had already learned of the early

days of the church

from Paul's unique perspective during their travels together, Luke's

list of additional

possible interviews staggers the imagination.

Certainly, Luke would have spent time with James, the brother of Jesus

and leader of

the Jerusalem church (21:18-19). There were many members of Jesus'

family who would

still have been available with whom to speak. Mary was, perhaps, still

living, and Jesus'

siblings, including Jude, may also have been available.

Some of the twelve apostles may still have been serving in Israel, and

most of those

who were elsewhere, including Peter and John, would have likely returned

to Jerusalem

over the course of two years for at least one pilgrim festival.

Furthermore, the apostles'

wives and families may not have always accompanied them on their

journeys and may

have been available.

Some of the original Hellenistic Jewish deacons (6:5) may have still

been in Israel.

Luke certainly spent time with Philip, who lived in Caesarea (21:8-10).

In addition, whether they first met during this time in Israel or later

as coworkers in

Rome (Col. 4:14; Philem. 24), Luke and Mark were well acquainted. There

is no question

that in writing both Luke's gospel and Acts, he was reliant on Mark's

written testimony

(the gospel of Mark) as well as oral reminiscence of his early Christian

experiences.

The gospels and Acts are strewn with the names of additional individuals

with whom

Luke may have had opportunity to speak and get their personal accounts:

Mary

Magdalene (Luke 24:10), Mary, Martha and Lazarus (Luke 10:38-42), the

unnamed lame

beggar (Acts 3:2), Nicodemus, Joseph of Arimathea (Luke 23:50), Tabitha

(Acts 9:40),

Aeneas (Acts 9:33), Rhoda (Acts 12:13), Agabus (Acts 21:10), the priests

who came to

faith (Acts 6:7); Cleopas and his Emmaus companion (Luke 24:18);

Bartimaeus (Luke

18:35); Zaccheus (Luke 19:2) and additional dozens.

Indeed, one may only speculate on how many of the five hundred witnesses

of Jesus'

resurrection (1 Cor. 15:6), or of the seventy emissaries Jesus had

appointed (Luke 10:1),

or the "Pentecost three thousand" (Acts 2:41) were subject to Luke's

careful

investigation. Both of Luke's volumes teem with concern for the

"personal touch." In

Acts alone, Luke references over one hundred people by name!

Protagonists, antagonists,

minor characters and bystanders all are recorded for posterity by this

conscientious

historian.

In short, there was no scarcity of potential sources Luke may have

tapped to compile

his two-volume work.

Luke's time in Israel also accounts for his tremendous attention to

geographical

detail. As Paul's missionary companion, Luke's ability to conjure up the

geographic

details that characterize his European travelogues is not at all

surprising. Yet it is his

strikingly vivid rendering of Galilee, Jerusalem, the Temple, Samaria

and Israel's coastal

cities that reveal Luke's first hand knowledge of Israel.

SPEECHES IN

ACTS

As becomes obvious on first reading,

a vast portion of Acts (roughly one third) is

composed of various sermons and speeches, primarily those of Peter, Paul

and Stephen.

Indeed, based on the percentage of narrative content dedicated to the

speeches, perhaps

Acts should have been assigned the more precise title, Selected Acts of

a Few Apostles

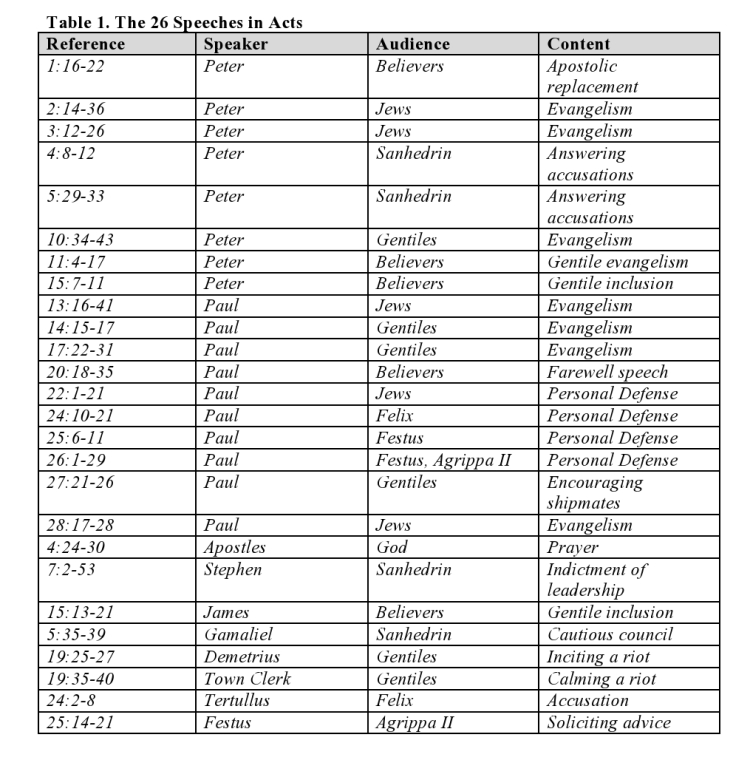

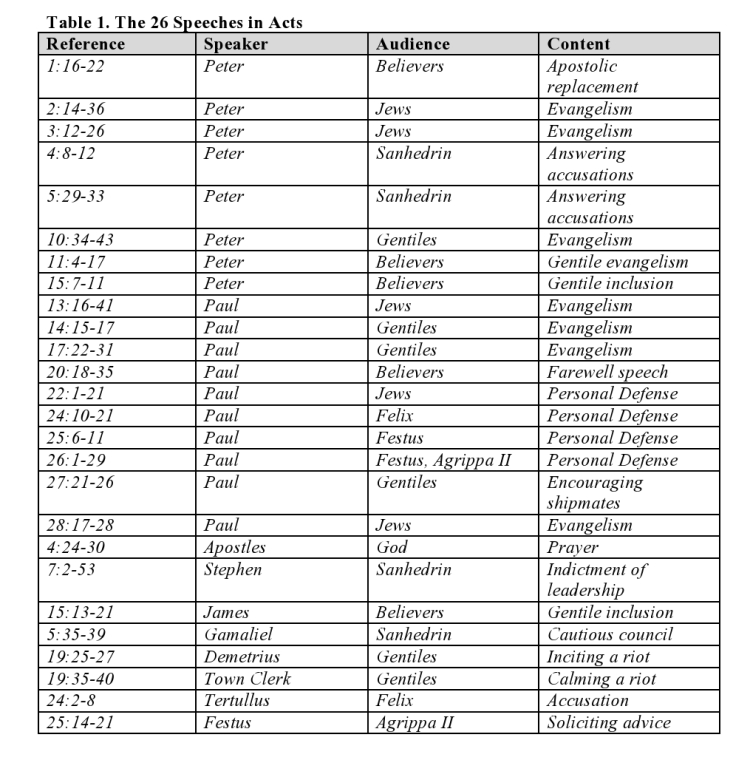

and an Extra-Large Assortment of their Sermons (see Table 1).

It is in the record of these speeches that Luke's qualitative

faithfulness to his

historical sources shines through. Luke's usual method is to quote a

portion of the

original speech and then summarize the remainder using his own words.

There is every

reason to attribute the quoted text of these speeches to either some

sort of written record

(although the presence of an on-scene "stenographer" is unlikely) or the

personal

reminiscence of the speaker himself or a member of his original

audience. Most of these

speeches were delivered on what, admittedly, must be described as

"memorable

occasions," which likely burned the content into the consciousness of

speaker and

listeners alike. This would have been particularly true in a culture

like Israel's, which so

highly valued the memorization and oral transmission of the instruction

of valued and

beloved teachers. (5) In addition, the Holy Spirit must have been

influential in the

preservation and recall of these messages.

Each speaker in Acts has his own distinctive voice: Peter, Paul, Stephen

and James all

qualitatively read very differently from one another, even when

addressing the same

broad themes or making reference to identical Old Testament prophecies.

Furthermore,

each speech is tailor-made for the particular audience to which it is

addressed. Peter

addressing the Sanhedrin is not identical to his addressing Cornelius.

Paul addressing the

synagogue reads very differently than when addressing the Athenians.

While it is doubtful that it would have been possible for Luke, decades

after the fact, to

accurately reflect the exact word-for-word text of every speech, it is

not at all improbable

that he accurately reflected the substance of each speech as originally

delivered. In other

words, we can be confident that what was eventually recorded was the

substantial gist of

what was originally spoken. It must be reiterated that Luke claimed to

be a conscientious

reporter of history and not a creative writer of fiction.

FOOTNOTES

1. Donald Guthrie, New Testament Introduction (Downers Grove:

InterVarsity Press, 1970), 354.

2. Ibid., 354.

3. Mal Couch, ed., A Bible Handbook to the Acts of the Apostles

(Grand Rapids: Kregel, 1999), 369.

4. Mal Couch, ed., A Bible Handbook to the Acts of the Apostles (Grand

Rapids: Kregel, 1999), 369.

5. The entire complex corpus of Jewish oral law is built on this

memorization and oral transmission

from one generation of rabbis to the next. This corpus of oral customs,

traditions, edicts and verdicts

was not committed to writing until the second century AD, following the

destruction of Jerusalem and

the Temple, and the majority of the Jewish people’s exile from the land

of Israel.

STUDY

QUESTIONS

1. What is the evidence that Luke is

the author of Acts?

2. What is the evidence for the pre 64 AD composition of Acts?